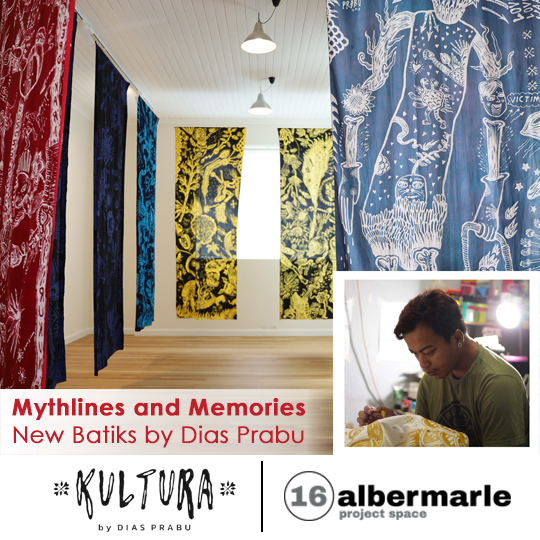

Mythlines and Memories: New Batiks by Dias Prabu

Published by Sugar & Cream, Wednesday 12 August 2020

Text by Elly Kent, images courtesy of Kultura by Dias Prabu & 16albermarle Project Space

Prabu’s Exhibition: Feb 29- March 28,2020 at 16albermarle Project Space

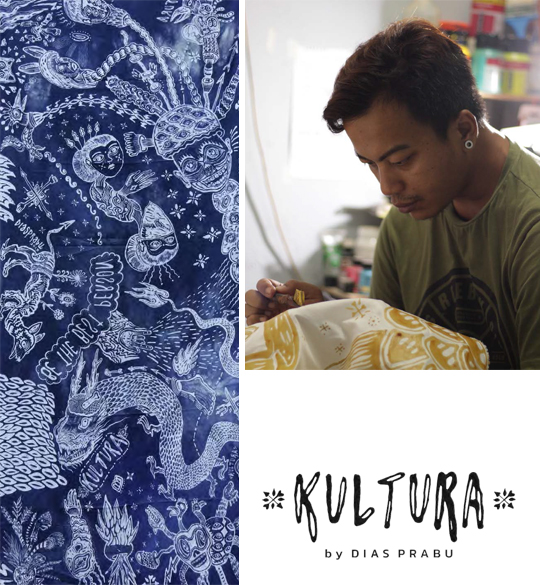

Brightly coloured and patterned batik is synonymous with Indonesia. But in the hands of Yogyakarta muralist Dias Prabu the medium becomes an expressive platform as he pours imagination and allegory, animals and text into spontaneous contemporary drawings made with wax on fabric. Often featuring symbols of national pride, the works are his way of making a contribution to the national dialogue around issues as diverse as environmental degradation, the extinction of species and the values Indonesia should follow as a complex land of over 17,000 islands with a large, ethnically diverse population.

See also the opening scene from Dias’ exhibition here.

Indonesia takes national values very seriously, enshrining them in its new constitution in 1945, in a moral code called Pancasila. This literally means ‘five pillars’ – monotheism, a just and civilised humanity, a unified Indonesia, democracy and social justice.

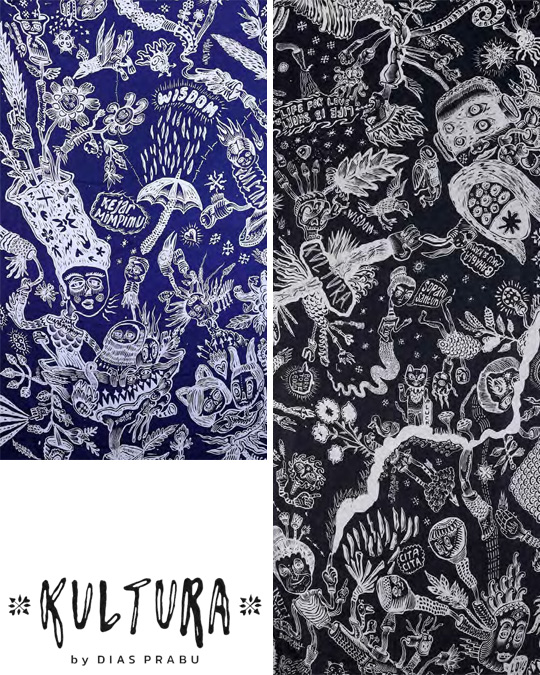

Paradoxical Mind 2019, 300 x 110 cm | Dias Prabu

Dias Prabu’s journey to batik was circuitous. In 2014, not long out of art school, he won a national competition for mural painting. Part of the prize was to paint a mural on a wall of the National Gallery of Indonesia in Jakarta, where it remains today. His mural painting took him to cities in Java, Aceh, East Kalimantan and to the northern parts of Indonesia.

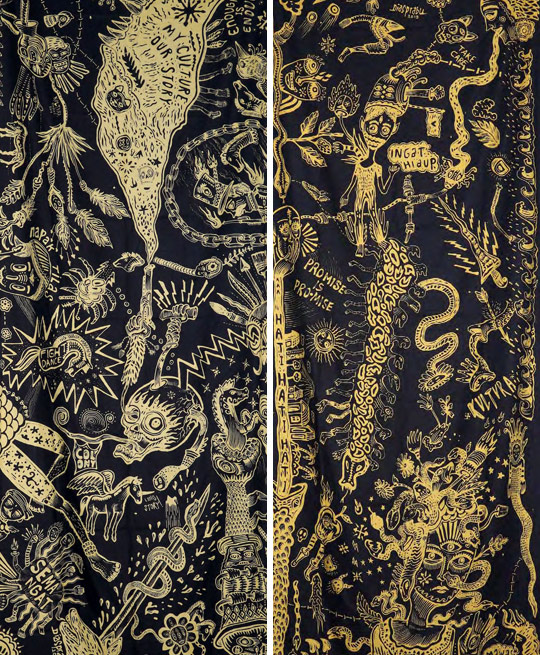

Berdikari (Independent) 2019, 300 x 110 cm | King of the food chain 2019, 300 x 110 cm

In 2017 he joined a Teaching Artists program, travelling to remote Natuna Island to work with school children on murals that investigated local stories, ideas and philosophies. It was there he began the Kultura Project, with a concept of Pendidikan Mural Pancasila, or Pancasila Mural Education, a play on the mandatory Pancasila Moral Education (PMP) implemented by schools during Soeharto’s New Order.

Imperfect behaviour 2019, 300 x 110 cm |Midnight myth 2019, 300 x 110 cm

In 2018 Dias undertook a residency at Kampung Batik Manding Siberkreasi, an organisation which draws on the philosophical basis of traditional batik to spread messages of harmony. It was here Dias had the idea of transferring his mural designs onto batik, learning to draw rapidly and skilfully with hot wax via a process called canting.

The guardian of life 2019, 300 x 110 cm | Manners from the forest 2019, 300 x 110 cm

Dias’s batiks at 16albermarle comprise two series. The first deals with traditional animals of Java, many either extinct or facing extinction. In the second, he explores childhood memories and the stories told to him by his grandfather. Although addressed to the Indonesian people, the moral and environmental messages in these batiks speak to people of every country.

Jaranan 2019, 300 x 110 cm | Introspection 2019, 300 x 110 cm

Processes of resistance: Dias Prabu’s batik for a new world view (written by Dr Elly Kent)

The rain has just eased as I make my way down the alley towards where Dias Prabu’s small home appears on the map. A neighbour sitting on her porch directs me to a narrow track and I find my- self with buildings to my right and a lush field of sugar cane, with excessively verdant edgings of banana trees, acacias and tall green grasses to my left. We are just a few kilometres from the centre of Yogyakarta, a city of over 4 million people, but all around is quiet and green. The bucolic urbanism – the kampung neighbourhood – is one of the many things that draws artists to the town they affectionately call ‘Jogja’.

Presented by Interni Cipta Selaras

Inside Dias’ home he emerges from the bedroom in the early afternoon, after working through the cool of the night. We sit down amidst the traces of the previous night’s efforts, a wok of brown wax, a canting pen and the 100m long stretch of fabric Dias is currently working on for a com- mission. He launches into a well-rehearsed autobiography; his undergraduate studies majoring in painting in East Java, post graduate studies at the famed Institute of Art in Yogyakarta, his practice in mural painting and success in competitions and then, more recently, his turn to batik. But I want to know more.

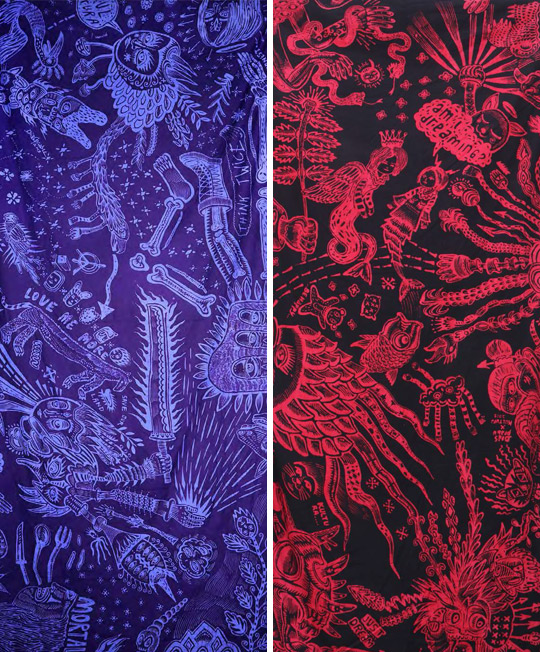

Blessing moment 2019, 300 x 110 cm | Shooting things 2019, 300 x 110 cm

I’m intrigued by this adoption of the traditional wax resist process, but also by Dias’ particular ap- proach to the practice, in which he largely eschews both pattern, repetition and abstract symbol- ism. Instead, he pours imagination and allegory, animals and text into spontaneous contemporary drawings made with wax on fabric. His work often features symbols of national pride and, he tells me, this is his way of making a contribution to the nation. This too, is an unusual position.

There are many modern-day batik artists in Yogyakarta–any foreign tourist wandering along Ma- lioboro Street will be invited into their studios, where traditionally esoteric symbolic motifs are often replaced by drawings of becaks or other figurative images. Indeed well-known contempo- rary artists like Heri Dono have turned to the form in their careers. These riffs on Indonesia’s most famous art form might often be regarded detrimental to the form, but the practice of incorporating observations of contemporary life is also a long tradition. The National Gallery of Australia’s enor- mous collection of Indonesian textiles includes a batik from the mid-20th century which features tanks and armoured cars, driven by warriors from the Javanese version of the Mahabarata legend, locked in battle with the Japanese. The clown figure Semar even parachutes into the scene.1

Dignity behind the sunlight 2019, 200 x 110 cm | Immortal Knowledge 2019, 200 x 110 cm

In his seminal writing on Indonesian art in the 1960s and 70s, Sanento Yuliman observed that modern art emerged in the midst of living art traditions that have strong social functions, thus modern and contemporary art in Indonesia were also expected to ‘be widely understood in soci- ety’.2 But since the fall of the authoritarian New Order imposed by President Soeharto from 1966 to 1998 and its attendant demands that artists produce apolitical works to valorise the nation, contemporary art that uncynically adopts the symbols of loyalty to the nation has fallen out of favour. Yuliman called the early proponents of this critical art practice ‘the restless ones’; their legacy remains strong.3

This places Dias in an unusual and complicated position. Indonesian contemporary art has tended towards subversive engagement with the idea of the nation, such as groups like Punkasila, a band of artists whose name plays on the five-pillars that Indonesia is founded upon.4 But following an average young Indonesian on Instagram, you might instead find them declaring their allegiance to the nation on the annual Youth Pledge Day. Perhaps Dias’ approach is more reflective of that majority who hold fast to the lessons imparted to them in school?

Purpose of life 2019, 200 x 110 cm | Love is long, life is short 2019, 300 x 110 cm

In 2017, Dias joined the inaugural ‘Teaching Artists’ program initiated by the Ministry of Culture and Education. He travelled to remote Natuna Island with a brief to investigate local stories, ideas and philosophies. There he spent weeks talking to locals, learning about local creative weaving processes and working with school children to reinterpret and reimagine the designs. This is where his mission to understand the stories of his nation took form, which then manifested in the Kultura Project. Dias began the Kultura Project with concept of ‘Pendidikan Mural Pancasila’, or Pancasila Mural Education, a play on the mandatory ‘Pancasila Moral Education’ (PMP) implemented by schools during the New Order. However, in Dias’ conception, the rote learning of ideological texts was replaced with ‘the investigation of local narratives…on diversity and tolerance which are then represented in a mural’.5

In 2018, Dias found an opportunity to implement his own version of PMP during a residency at Kampung Batik Manding Siberkreasi, in the hills south of Yogyakarta. This community driven organisation aims to draw on the philosophical basis of traditional batik to spread messages of harmony, whilst also utilising it as a vehicle (with the support of the Ministry of Communications and Information) for raising digital literacy in the community. Here Dias worked again with children and murals, this time to understand the ancient patterns and functions of batik and to design new symbols. But he also refined the batik-tulis, or hand wax-drawing skills, he had briefly encoun- tered in his undergraduate studies. From that experience, he has shifted his principles of PMP – albeit perhaps temporarily – into the realm of batik.

Luckyness unlimited 2019, 300 x 110 cm | Between happiness and identity 2019, 300 x 110 cm

The 15 works we see in the exhibition at 16albermarle Project Space today draw on two sources: Dias’ overriding concern that Indonesian society has lost touch with the wisdom of its forebears, and that consequently the fabric of the eco-system is threatened by human behaviour. While traditional batik has been used as a talisman to ward off such events on an individual and com- munal level, and the patterns imbued with motifs that symbolise the inherent connection between humans and the natural world, Dias’ works are instead spontaneous outpourings drawing on his personal aesthetic and his environment. Stylistically, they draw more from the Jogja ‘Agro-Pop’ paintings of the early 2010s, and the work of senior artists like Heri Dono and Eddie Hara, or more recently, Eko Nugroho and the Taring Padi collective’s enormous oeuvre of politically charged woodcut prints, rather than conventional batik.

The first time I read Dias’ own writings on his work, I was tuned in from afar to a full day of emer- gency broadcasts to my home-town in Australia, overwhelmed by a sense of impending doom after witnessing a summer of fire, smoke, hail and flood in Australia and Indonesia. Dias’ optimistic writing and positive mantras seemed naively cheerful as the globe reaches such a terrifying tip- ping point. Referring to the work Purpose of life, Dias evokes the Javanese proverb spoken often to him by his parents: ngunduh wong pekerti, which translates roughly to ‘you reap what you sow’. This he interprets with the inclusion of text reading Kejar mimpimu (Chase your dreams) in a field of light-hearted, cartoonish representations of smiling animals and humans in a teeming two-dimensional field.

Love and Care 2019, 300 x 150 cm | Priceless Dream 2019, 300 x 150 cm

Yet looking deeper there is a sense of restlessness, perhaps one more ambiguously defined than his predecessors. In King of the food chain, Dias depicts an ornately decorated Javan tiger, a spe- cies declared extinct in the 1980s, carrying a human in a tiffin. According to Javanese legend, Dias reminds us, the tiger will always do good for those who do good towards it, and vice versa. What if, he asks, the tiger were to return and reclaim its place at the top of the food chain? What would be the fate of humans?

Dias’ work carries for Australian audiences a pertinent reminder that is both hopeful and alarm- ing. As we emerge from a period of unprecedented danger of our own creation, will we choose to make amends with the environment on which we are entirely dependent, and to which we are completely vulnerable? Will we choose to respect the practices of elders that safeguarded our ex- istence on this earth for hundreds of thousands of years? Or will we continue our downward spiral of consumption, destruction and oblivion? Ngunduh wong pekerti.

Another side of human nature 2019, 300 x 150 cm | Heartworker’s pride 2019, 300 x 150 cm

Dr Elly Kent is a translator, writer, artist and editor of the Australian National University’s New Mandala blog on Southeast Asia. She is a Visiting Fellow in the ANU’s Centre for Art History and Art Theory, researching contemporary and historical art and design practices across Indonesia.

1 Skirt cloth (Kain Panjang) 1942-45. For more details see https://artsearch.nga.gov.au/detail. cfm?IRN=96249

2 Yuliman, Sanento. “Seni Lukis Di Indonesia: Persoalan-Persoalannya, Dulu Dan Sekarang (Budaya Djawa, Dec 1970).” in Dua Seni Rupa, Sepilihan Tulisan Sanento Yuliman, edited by Hasan Asikin. Jakarta: Yayasan Kalam, 2001.

3 Yuliman, Sanento. ‘Kemana Semangat Muda’ in Dua Seni Rupa: Sepilihan Tulisan Sanento Yuliman. Jakarta: Yayasan Kalam, 2001. (Original text from mid-1980s)

4 The ‘Pancasila’, the five ideological principles on which Indonesian nation was founded in 1945, are in brief, godliness, just and civilized humanity, unity, representative and consensual democracy, social justice. These principles are memorized by school children and referred to by leaders at every level of society.

5 Andika Andana, Progress baru Dias Prabu melalui Kultura Project dalam Kriya Rupa, (unpublished) Yogyakarta, 2020

682

14/07/2025

682

14/07/2025

RIVER ISLAND VILLA BY JISHANG SPACE DESIGN

A sophisticated, cozy, and nourishing residence, the River Island Villa by Jishang Space Design is a natural beauty project located in Wenzhou City, China.

read more 512

14/07/2025

512

14/07/2025

THE GIORGETTI MASERATI EDITION UNVEILED AT GIORGETTI ATELIER NEW YORK

Giorgetti Maserati Edition debuts at Giorgetti Atelier in New York: a celebration of Italian craft and heritage.

read more 42.71K

11/07/2025

42.71K

11/07/2025

PELUNCURAN PERDANA LEGANO HOME MENGGANDENG AGAM RIADI DI ST REGIS RESIDENCE JAKARTA

Peluncuran perdana LEGANO HOME menggandeng Agam Riadi di St. Regis Residence Jakarta: menyatukan kemewahan dan jiwa dalam sebuah ruang.

read more 16.02K

04/07/2025

16.02K

04/07/2025

URBANJOBS UNVEILS INTERIORS FOR THE SCALLA RESTAURANT

SCALLA, a posh restaurant with a Mediterranean flair located in Istanbul's famed Beykoz neighborhood, has its interiors unveiled by URBANJOBS.

read more 75.20K

10/01/2025

75.20K

10/01/2025

W RESIDENCE IN SOUTH JAKARTA BY MICHAEL CHANDRA

Michael Chandra, founder of MNCO Studio Design has created the W Residence with an aesthetically pleasing, practical, and pleasant home from all...

read more 42.71K

11/07/2025

42.71K

11/07/2025

PELUNCURAN PERDANA LEGANO HOME MENGGANDENG AGAM RIADI DI ST REGIS RESIDENCE JAKARTA

Peluncuran perdana LEGANO HOME menggandeng Agam Riadi di St. Regis Residence Jakarta: menyatukan kemewahan dan jiwa dalam sebuah ruang.

read more