Matahari- Sarang I, Yogyakarta

Published by Sugar & Cream, Wednesday 02 November 2016

Text by Lorenzo Poggiali, Photography by Angelo Morra

Filippo Sciascia Solo Exhibition – October 27 – November 06, 2016

During one of our nocturnal colloquies – if truth be told with me more than anything trying not to let her fall into one of the formidable Renaissance traps of Santa Maria Novella, nudging her along with lile pats on the arm as one would with a friend – Nan Goldin cracked an enormous smile at the menon of Luigi Ontani, considering him a true arst. It’s an opinion I share without myself making any claims to being an exclusive maître à penser. It would take a good while to go fully into the maer of who is a true arst according to Nan Goldin, but with a heinous succinctness I would dare to say he who unites art and life, or rather who brings them together by adopng a coherence between thought (strong) and acon.

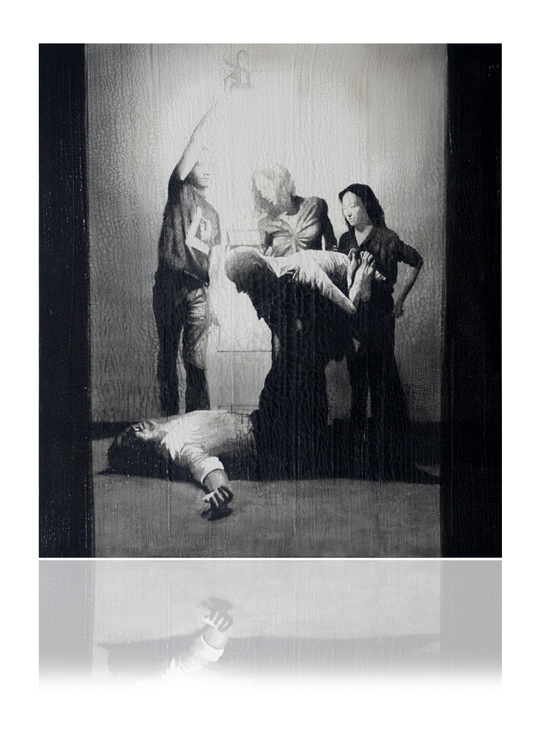

Filippo Sciascia

The next evening in the gallery she dwelt at length on a work by Filippo Sciascia, even touching it, asking me several mes, “Who is this?” She really liked it; she really liked it a lot. Not long had passed since the news that Luigi Ontani and Filippo Sciascia had struck up an intellectual fellowship, and sll less since this intense and impressive exchange led them to do a show together in Naples at the Archaeological Museum: Bali Bule. Filippo Sciascia, Ashley Bickerton and Luigi Ontani (2013/14). Matahari (2014) was Filippo Sciascia’s first one-man solo project in Italy since his return home, aer having harvested Asian appreciaon from his base in Bali. It was a corpus that took its cue from the works presented in Naples. We need to bear in mind that Filippo Sciascia sees his work as a connual evoluon. So much so that Matahari featured less recent works as natural

Gremano Esia_co 28, 2014, oil on paper mounted on iron, 35 x 22 x 18 cm

connecng links, basing himself on the assumpon that the quality of thought can be externalised in art in the most disparate ways and that he favours some of these, among which painng is the chief but not the only way, as we can appreciate in this show. He indeed says of it: “I did sculpture bydoingpainng”.

Filippo Sciascia handles the conceptual approach while always keeping the painng as the core of the work, even when in terms of containment we are looking at installaons and objects. Sciascia’s relaonship with painng is always condioned by the use of other media – especially cinema and photography.

The ease of moving within the history of art and the quality of the relaonship with the territory of life and with his own roots encourage Sciascia to pracce an art that is capable of yielding the certainty of the past and a gaze towards the future, a cultured and demanding art as an andote to allusive and unwing maîtres-à-penser. I can grasp the closeness to Luigi Ontani. Nor would it be displeasing to Crispol, who staunchly upheld that the capacity of an arst was to measure himself through appraisal of his ability to restore the meaning of our mes and, at the same me, to influence contemporary arsts. I don’t intend to go into details on either aspect.

I can’t get either Pasolini or Victor Man out of my head, but I don’t want to quote them out of place. From Pasolini I would take the radicalism, whereas in Victor Man what strikes me is the admiraon we share for the work of the Rumanian arst. Leaving aside the formidable capacity for addressing muted colours (and for mung them), recently I

Gremano Esia_co 35, 2014, iron, sea horses, golden oil paint, 33 x 27 x 22 cm

laid my hands on an inspired arst’s book of his about an unknown seventeenth-century arst, with whom evidently Victor had entered into a spontaneous harmony – even more Roman than Romanian – culminang in the curious scene of the explanaon by me, on his own invitaon, of his works which they had just asked him about.

The series of the hands was sparked by the surprising discovery of local sculptures inherently linked to the Byzanne iconographic tradion, abstract and not naturalisc, but devoid of all jusfying contaminaon, to which he cannot of necessity be indifferent since it is ineluctably bound up with his own Western legacy. It also comes from the extension of that wonderment to the iconography of the old zodiacs in which the rings of animals were arranged around men in the originals, whereas in Sciascia’s work they move around the fingers, and hence the hand, curiously linking up with the concept of self- portrait that Sciascia resorts to: namely the hand as the principal instrument of the arst’s acon, thereby restang its centrality.

Sciascia’s interest in the zodiacs is none other than the connuaon of his exploraon of the stars, a synecdoche through which he refers to the light and the study of the same, from cinema to photography, through to the physical reacon in contact with the human percepve process in which the pineal gland plays a decisive role. This harks back to the interest in the universe, resorng each me to expedients that are not reduced to the mere repre- sentaon, for which a high-resoluon photo would suffice for example. He instead follows his own temperament, drawing and painng in a classical mode, or through objects and installaons that are none other than the exercise of doing sculpture through painng.

Lux Caravaggio, 2008, oil on canvas, 190 x 180 cm

While the lesson of conceptual art manages the radicalism of thought, progressively suppressing sensive data in the (non) formal results, Sciascia sasfies his own conceptual poecs, taking over an object and modifying its use, aer Duchamp that is, but rather than through the readymade by definion, through classical painng or the installaon dimension of this, in which the draughtsmanship and the pictorial gesture are never absent.

A constant shiing between Western history, the origins of the arst and the reality of Bali; a world awash with spiritual condioning where, for example, the recurrent explosion of the volcano catapults the experience of the arst into a dimension where, all of a sudden, the palms turn white as if laden with snow: the essenal datum connues to be surprise, wonder.

Starng from the central group of large sculptures, all the works are entled Gremano Esiaco, sequenally numbered: in this way the arst intends to uninterruptedly condense classical Greek and Roman iconography with Indonesian spirituality, to harness the weight of the history that he comes from and which belongs to him with the everyday of one of the most spiritual places in the world. And we should remember that such pernent adherence to this iconography was sparked by the comparison with the collecon of the Naonal Archaeological Museum of Naples, connuing then along the strand of ‘poor Baroque’, an expression Sciascia resorts to when speaking of these works that are only apparently unadorned, humble, commonplace, but actually glier with an abundance of refined detail.

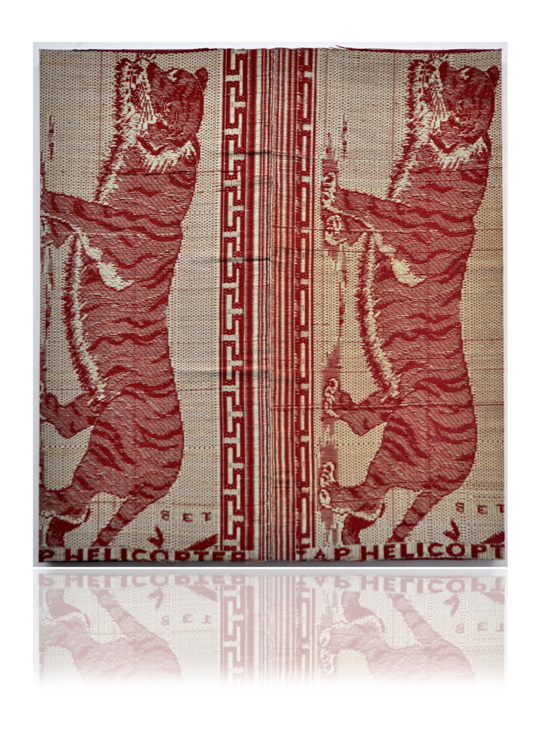

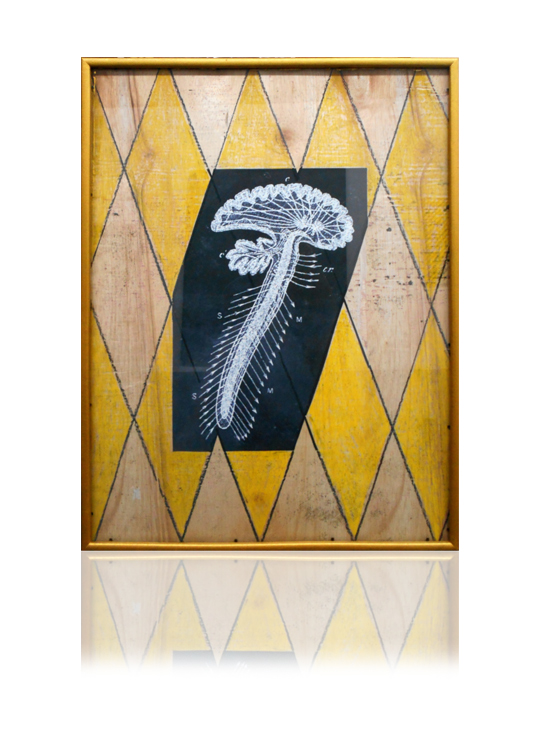

Araldica 23, 2016, two floor mats on wood, 170 x 150 cm

The result of Sciascia’s works is the journey, the synthec restuon that art offers, from Western culture to the impact with Indonesia, more precisely with Bali, as a unique and unrepeatable moment. In Gremano Esiaco 8 (2013), for example, figures from western culture are laid upon a sculpture originang from the Island of Flores, but what is truly original is the reading through which we have to approach it. The rear of classicism is in effect the conceptual front side of the sculpture, since the leaf is the present, because it comes from Bali, its soul linked to the Hindu temple and its shape rising in corners reproduced by the lines of the leaves. This Bali mof is confirmed by the re- proposal of the model of yellow and black lines that come together exactly half-way in the works on wood, in which he oen inserts Western icons such as Donatello’s David constructed by carving a beehive, posing dualism and oscillaon between roots and territory, West and East.

A propos this it is also pernent to menon the pictorial works on panels on the model of Brunelleschi, inlaid with wood from Bali, bearing a painted portrait. Sciascia cites his being an adopve Florenne through Brunelleschi, natural icon of the Western heritage that Sciascia comes from, bringing it together with wood coming from Bali and having been carved there.

Sciascia defines himself as a contem- porary arst that looks to the past, capable of drawing on his adopve land while valorising the Western culture in which he was born and arscally trained. Two sides coexist in these sculptures, just as duality disnguishes not only the human being but also nature in the alternaon of day and night, hot and cold, rain and sun, and is indeed one of the leitmofs of the enre show. The two sides appear everywhere: we come up against a connual symmetry, from the leaves to other mofs on wood or even on canvas.

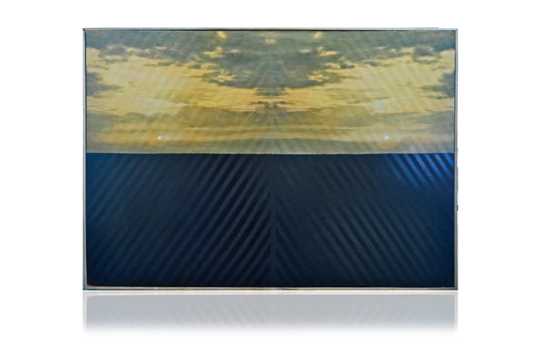

Matahari Terbit, 2014, oil on canvas, 115 x 170 cm

In front of the sculpture with the bells (Gremano Esiaco 3, 2013) Filippo Sciascia says “It’s a bit like doing Arte Povera taking in the Baroque on the way”: because visually it is poor, since these are humble materials, but in actual fact they are rich in ornament and facets. One has only to look at the trunks of the sculptures, real black fern trunks that the arst collects, redolent of Greek columns, adorned and interwoven with the associaon with bells as objects of the ritual of prayer present in every home, so rooted is spirituality and devoon. The painngs pursue the same poec: they are cracked to give the idea of being poor, but only visually, because in actual fact they harbour a lengthy labour of sedimentaon and construcon of the image.

Running through the show Matahari were the concepts of duality and encounter between the Western and the Asian worlds. These are implemented both through the aribuon of new meaning to objects whose original purpose is altered, in associaon with others – in line with the need to simultaneously display on the one hand the past and Western roots and on the other the contemporary and everyday spirituality of Bali – and through the juxtaposion of western iconography and material from Bali for the same conceptual sasfacon.

Consider the radical choice of living in Bali, the isolaon in a world marked out by the rhythms of prayer, devoon and spirituality, by the bells and the shrines in every home.

Lumina Araldica 7, 2016, oil on paper on wood, 71 x 54 cm

I like, for example, to think of the work in barbed wire with seahorses, Gremano Esiaco 35 (2014): on the stalls of the Bali markets the barbed wire is coiled in bundles. The iconography recalls the passion of Christ, but in Bali no-one pays any aenon to this detail, which instead leads Filippo Sciascia to garner that charge of significance and overturn it into a pagan dimension, redesigning the contours by using real seahorses – symbol of the god of the sea for both Asian and Greek culture – hence underscoring the dual polarity of the show: Asian culture and classical culture.

The same holds for the work done with the bamboo basket used to carry the dead, its use altered to contain a new meaning: a face is applied above the centre of the basket, opened up like a surface and freed from the interlacing, a face like the sun, which in Balinese is ‘mata hari’, that is the eye of the dawn and hence the sun, expression of a parcularly spiritual language that gave its tle to this project of Filippo Sciascia.

Lumina Araldica 20, 2016, oil on canvas, 200 x 110 cm

This essay by Lorenzo Poggiali was first published in the book Filippo Sciascia, Matahari, ExMarmi Complesso Post- Industriale Pietrasanta (Florence: 2014).

1.06K

01/07/2025

1.06K

01/07/2025

VIVERE GROUP INVITES YOU TO "DESIGNED FOR LIFE" AT ICE BSD

VIVERE Group Invites You to "Designed for Life" at ICE BSD from July 2-6, 2025: inspiring design talks, live entertainment and networking

read more 1.13K

01/07/2025

1.13K

01/07/2025

ADRIAN GAN – MENENUN GAGASAN

Simak perbincangan eksklusif kami dengan Adrian Gan seputar memaknai ruang kreatif dalam Menenun Gagasan.

read more 26.66K

03/06/2025

26.66K

03/06/2025

PAOLO CASTELLI @ MILANO DESIGN WEEK 2025

The opening of Paolo Castelli's Milan showroom during Milano Design Week 2025 showcases a collection that blends Castelli's elegance, tradition, and...

read more 12.05K

17/06/2025

12.05K

17/06/2025

JAIPUR RUGS X PETER D’ASCOLI PRESENTS THE GILDED AGE COLLECTION (2025)

The Gilded Age collection by Jaipur Rugs X Peter D’Ascoli channels the decadent glamour of 19th-century design into bold, hand-knotted rugs that exude...

read more 74.59K

10/01/2025

74.59K

10/01/2025

W RESIDENCE IN SOUTH JAKARTA BY MICHAEL CHANDRA

Michael Chandra, founder of MNCO Studio Design has created the W Residence with an aesthetically pleasing, practical, and pleasant home from all...

read more 33.40K

16/05/2017

33.40K

16/05/2017

A Spellbinding Dwelling

Rumah milik desainer fashion Sally Koeswanto, The Dharmawangsa kreasi dari Alex Bayusaputro meraih penghargaan prestisius Silver A’ Design Award 2017.

read more