CAN’S Gallery : Solo Exhibition by J. Ariadhitya Pramuhendra

Published by Sugar & Cream, Friday 18 May 2018

Curatorial text by Hendro Wiyanto, images courtesy of Can’s Gallery

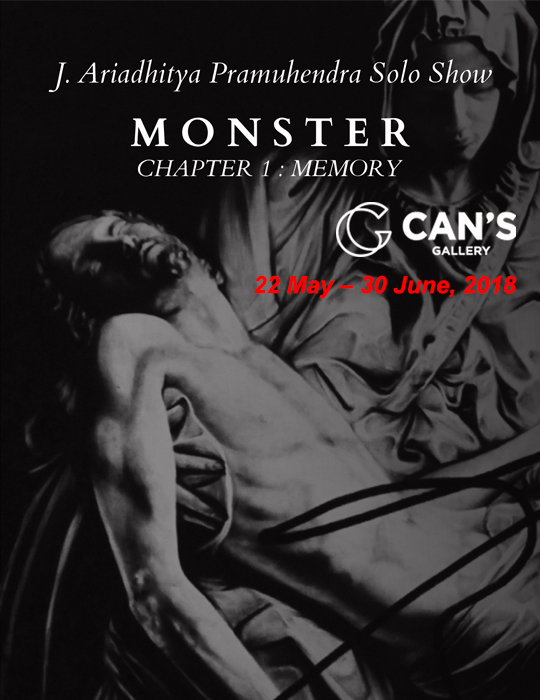

MONSTER Chapter 1 : Memory – May 22 – June 30, 2018

BELIEF

The Prince and Salvator Mundi

The art world was buzzing with excitement at the end of last year. Prince Mohammed bin Salman, crown prince of Saudi Arabia, was rumored to be the new owner of Salvator Mundi painting. He recorded the highest bid for the artwork listed under Lot 9-B, at a Christie’s Auction, New York, United States (15 November 2017). This genius work of Leonardo da Vinci, estimated to be made between 1495-1504, broke the art sale record in the history of painting auction. The price was an incredible amount of 450.3 Million US dollars, or about 6.1 Trillion Rupiah. Da Vinci painted the figure of Christ as the “savior of the world”, a blonde bearded Aryan, his right hand points to the heavens, while his left hand is holding a glass orb.

What is the meaning of Salvator Mundi for an Arab Prince? The work of Leonardo represented the Christian belief of God presence in the world as the Christ. Under this belief, the “historical” Christ possessed both the humane and the divine characteristics. The biblical subjects in Leonardo’s artwork depicted not only the “visual truth” but also the “narrative truth” of the work itself. Famous for being a maestro of portraits and his knowledge of the “divine proportions”, Leonardo believed what he painted as the truth. The multi-talented painter diligently investigated Biblical stories to gain accuracy and validity of the theme he was painting.

Collecting religious art objects and believing in the narration of the said art object are two different things. Religious paintings are images containing certain symbols or markers of “religiosity”. The intention and representation of religious belief—which gave birth to religious art object—is not a movable object nor could it be just merely attached to the owner of the painting. Believing the narrative truth of a religious painting, which is the relation between Leonardo and his painting, is certainly first and foremost, a personal matter. If Salvator Mundi was more of the representation of the artist’s belief, then the Prince’s fondness to the painting more or less signifies his response or interpretation to a denotation. In the first one, the symbol is nearly identical to the original meaning or denoted representation (as representatum or denotatum); in the second, the denotation is a process of interpretation or appreciation to the object (as interpretant). Experts of semiotics would usually state; representation always contain a more fundamental characteristics compared to interpretation.

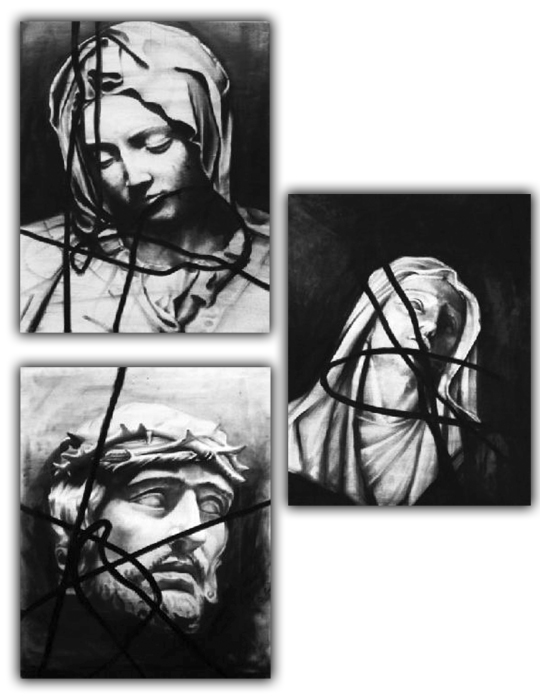

Potrait No. 1, Potrait No. 2, Potrait No. 3

The “Religiosity” of the Monster

Pramuhendra has been interested in painting religious themes—especially Christianity—since several years ago. We could recall, this interest could be brightly seen in his first solo exhibition (2008), with appropriative works referring to the psychological complexities of the dramaof the Last Supper (1495-1497), a work of da Vinci’s.

Da Vinci’s work depicted the scene of Jesus’ last supper with his disciples and the various shrouds or mysteries regarding the sense of “trust”. In the domestic art scene, this exhibition was recorded as having shown the appropriative characteristics of Pramuhendra’s works with realism and black and white that was created, using charcoal. He maintains this charcoal and realism portrait painting technique until today.

He is an artist who, since the very beginning, has been moved by figure representatives and realism imageries. The tendency of art to return to representation such as Pramuhendra’s work, is a common tendency that could be observed on young artists in post-formalism Bandung, which was about the entire decade of the 90’s of the last century. But the tendencies in the 2000’s on “post-post-formalism” reaffirmation set it apart from the previous era. A more recent visual art tendencies are mainly intertwined with the advancement of information technology and the increasingly massive influence of cyber virtuality in the artistic world. Young contemporary artists of the 2000’s Bandung welcomed this global phenomenon by presenting pseudo-personal video art, conceptual arts, mechanical-electrical objects, new abstraction-digital-photographic imageries, performative and appropriative codes on paintings, universe of narrative-comical drawings, urban world parodies, et cetera. Reality is not something “lived in”, if we use the terms used by artists of the previous eras. Instead, reality is incarnated into a set of denotations without codes or backgrounds, and this set of denotations is no other than reality or a game arena, a novelty and fun for the artist.

Through the depiction of his own figure with various background of places he had never visited, at the time Pramuhendra, for instance, presented the shadow of “identity” detached from the substances of portrait painting tradition that signified the belief of modernist artists in the previous era. He painted the portrait of himself like a stranger, a boy of a new Java—posing in politeness or becoming a tramp wearing a formal suit—who is lost in the iconic courtyard of foreign countries (“Bandung Invasion” exhibition, Canna Gallery, Jakarta, 2008). To borrow the title of an exhibition several years later, the tendency to present this sort of identity puns seems to be the signs of the loss of direction of the identity formation (“No Direction Home” exhibition, National Gallery of Indonesia, Jakarta, 2010).

If in the appropriative Last Supper a few years ago (Exhibition in Cemara Gallery, Jakarta, 2008), he seemed to want to place himself as an integral part of the artwork narrative truth, identifying his self with dramatic subjects in the painting, he has now let go of this tendency. The search of image through a monster named the virtual world is what Pramuhendra chose to delay or even ignore his own religious intentions.

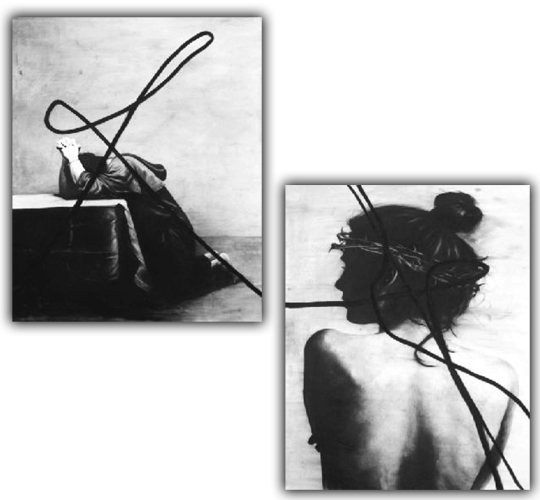

Empty Heaven & The last dance

Like what he stated, back then the charcoal series of work themed the Last Supper was “living in the theme”, the artworks in this exhibition was made through random searches on images or signs of “religious” in the virtual world. Put into language in different expression, we could say that the first was about living in the psychological identity, whereas the second one was more semiotics on the denial or delay of the identity.

The identity delay in the world of semiotics takes place through interaction with the virtual world. The virtual monster is the bytes we are consuming as an unlimited interpretant object. Dealing with such monster, instead as an artist who believe in the truth of religious images he paints, he is a consumer of denotations. His identity is a non-identity, an identity with an unlimited iconicity.

Like the event in the auction hall when the Prince appraised Salvator Mundi with his pocket of dollars, Pramuhendra considered religious images in the artworks in the monster’s belly were some sort of an abundance of pocket of bytes. “Pieta”, “Last Supper”, “crucifixion”, “the walk of the cross” or “thorns crown” are sets of bytes.This digital unit measure is the monster’s “religiosity”. The object becomes an imagery, the imagery becomes a symbol, and the symbol becomes a simulacrum. Enthralled by this kind of “religiosity” are the audiences of “Avengers: Infinity War” who cried when their superhero figure perished.

The other monster virtuality is no other but the version circulation, a version without limits. Into this world of version, he now immersed himself in.

After The Nails

Surface Image Ageman

Pramuhendra is very familiar with these kind of religious images since his childhood. Back then, in his Catholic family he often observed his father recreated in drawing the famous Pieta sculpture on a sketch book at home. The pages of the sketch book were filled with the drawings of these kind of imageries: the sculptures of Michel Angelo, paintings of da Vinci, Raphael, paintings on the crucifixion of Jesus made by nameless painters. The image of the death of Jesus on the lap of Mother Mary apparentl became one of his favorites. It’s what the Javanese said as a scene of pangkon (sitting on the lap), the ability to bear bereavement by holding the corpse of the deceased family member of close friend after it was cleaned. This imagery of pangkon famously known as Pieta became one of the imageries that stuck to his memory until today, whether he likes it or not. It probably was the reason why the appropriation of Pieta sculpture became one of the big sized two-dimensional paintings in this exhibition.

The habit of drawing Pieta was often done by his father in the dining table, as Without knowing exactly what his father intended by reproducing these religious images, he became familiar with observing European paintings of Christianity that are popularly reproduced. He also saw these images at school, at home, and of course, in the church. And later on, in Hollywood films.

He cited the Javanese perspective regarding religion. The religion (agama) is an ageman, which is a kind of suit that describes a person’s diginity. But when religion is considered as ageman, the meaning goes deeper rather than just a mere garb that covers the body, because religion—just like clothing—should fit the wearer when worn.

Before The Dawn & Maria

What is the most titillating in the perspective of religion as an ageman or as a clothing? For Pramuhendra, one of the most obvious thing from the symbols of religion or Christianity is its visual imageries. These visual narratives certainly cannot be fully separated from the narrative truths it contains, as a figure in (world) history, as a symbol (of divinity), the unspoken (from the sense of belief), the meaning of mystery (of belief or faith). But on the other hand, as a product of imagery, the visual narrative could also be perceived as a narrative on the beauty of ageman as though it is a clothing. As an artistic object, clothing could be seen as something detached from the wearer.

When in the appropriative Last Supper artwork series Pramuhendra presented and stripped down his own figure, physically taking off his clothing and be present within the dramatic scenes, now he used the most outer layer from his Catholicism ageman or clothing, without identifying his own religious intentions in the images. Imagery fragments of his habit in living in the passio, or the renarration of Christ’s way of suffering that has been the ageman of his Catholicism is entirely downloaded now from the virtual monster. For Pramuhendra, this involves something more instant, which is selecting the image artistic imagery, instead of considering the subjective religious experience.

Left, Middle, Right

Indeed, the traces of appropriation through the depiction of self-portraits such as in the series of Last Supper are not entirely gone. In this exhibition we are still witnessing his own self portrait wearing the crown of thorns, or in other works depicting him as a figure in private repentance. Another one, the appropriation works on big sized canvas depicted the scene of an artist washing his feet with a background in the form of a fragment of the Night Watch (1642) painting by Rembrandt. Is this some sort of a way to make a parody of his psychological identity with a popular iconicity we could easily find in the virtual world?

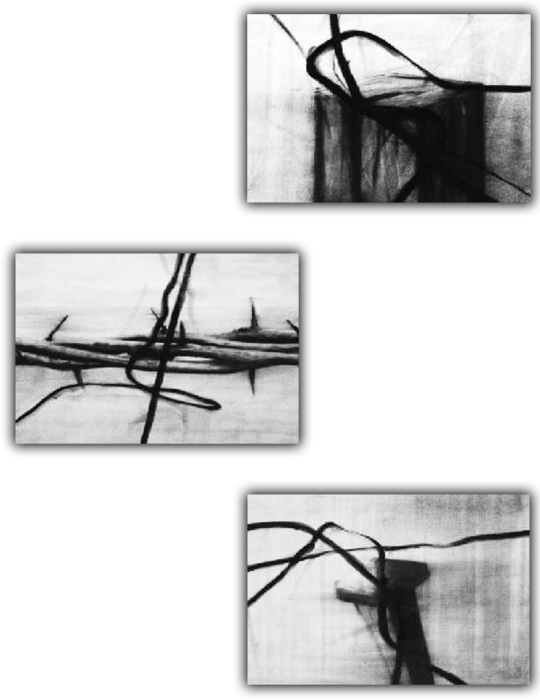

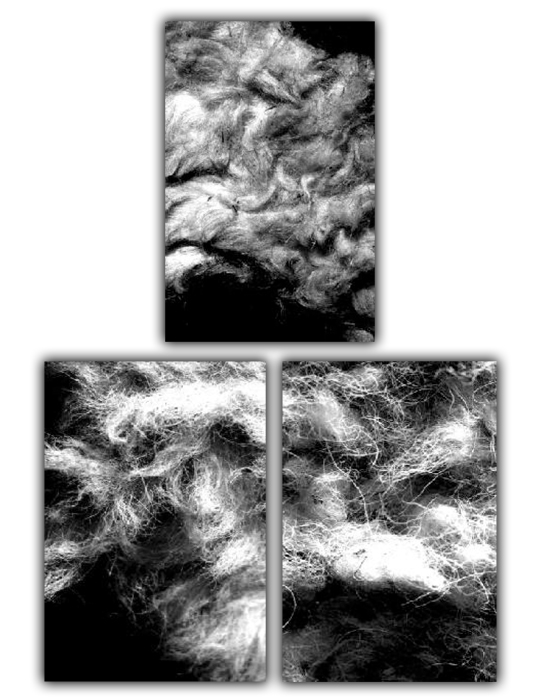

There are other elements that need to be paid attention to in Pramuhendra’s latest series of works. We are seeing long thick lines like knots of ropes that are left to disturb the work’s image of wholeness. these lines are extreme exaggeration of the lamb fur imagery, objects and means he had used for the last couple of years to create the “narrative truth” abstraction in the Lambskin (2016) series of works. In the tradition of Christianity, Christ is depicted as a shepherd, sacrificing himself for the lambs.

The Believer

We understand that a symbol has no limit to be perceived as a symbol. There is always something obscure regarding what and what we cannot call a sign. In these works of Pramuhendra, for example, the ambiguity stated: can we consider these works to be entirely related to “artistic truth” or on the contrary, a shrouded apology to affirm belief toward the “narrative truth?”

A symbol is always expanding and shrinking or moving in between the representation and interpretation, the background of meanings that the artist desires and the interpreters perceive. So are the religious symbols Pramuhendra had worked on in this exhibition, which became the field of tensions between the shrouds of belief or the representation of the artist’s faith and its semiotic suspension.

Night of Arrestment

Perhaps unconsciously, what Pramuhendra presented in this exhibition are appropriations of the drawing activities his father used to do, that he witnessed nearly all the time in their old home. The appropriation is operating in a level that is not entirely conscious, just like when in the past he wasn’t always aware on the relation between an image with belief on the truth narrative believed by the drawer, his father.

Like each ageman that basically acknowledges and celebrates its own transcendent mystery—like Umberto Eco once expressed—it seemed that the artist’s intentions also hold a secret and discreetly celebrates its own deviations.

St. Luke, St. Peter, St John

76

14/03/2026

76

14/03/2026

WILSEN WILLIM PRESENTS A CONTEMPORARY VISION OF EID DRESSING WITH RAYA 2026

Wilsen Willim hadirkan Raya 2026: busana lebaran kontemporer yang elegan dan fleksibel.

read more 74

14/03/2026

74

14/03/2026

ENJOYING NGABUBURIT AT JAKARTA PREMIUM OUTLETS THIS RAMADAN

Jakarta Premium Outlets introduces a relaxed way to enjoy ngabuburit, from festive shopping and art installations to iftar moments this Ramadan.

read more 10.06K

23/02/2026

10.06K

23/02/2026

IKAT INDONESIA BY DIDIET MAULANA X ZEN TABLEWARE: PINGGAN SWARANA COLLECTION

Piranti makan cantik “Pinggan Smarana” karya IKAT Indonesia by Didiet Maulana dengan Zen Tableware terinspirasi dari keelokan motif tenun Nusantara...

read more 7.83K

25/02/2026

7.83K

25/02/2026

MOIRE BESPOKE RUGS CELEBRATES A NEW CHAPTER IN DHARMAWANGSA

MOIRE Bespoke Rugs opens its doors in Dharmawangsa area on Thursday, 29 January 2026, offering a fresh space, a new collection, and a celebration of...

read more 83.44K

10/01/2025

83.44K

10/01/2025

W RESIDENCE IN SOUTH JAKARTA BY MICHAEL CHANDRA

Michael Chandra, founder of MNCO Studio Design has created the W Residence with an aesthetically pleasing, practical, and pleasant home from all...

read more 44.85K

11/07/2025

44.85K

11/07/2025

PELUNCURAN PERDANA LEGANO HOME MENGGANDENG AGAM RIADI DI ST REGIS RESIDENCE JAKARTA

Peluncuran perdana LEGANO HOME menggandeng Agam Riadi di St. Regis Residence Jakarta: menyatukan kemewahan dan jiwa dalam sebuah ruang.

read more