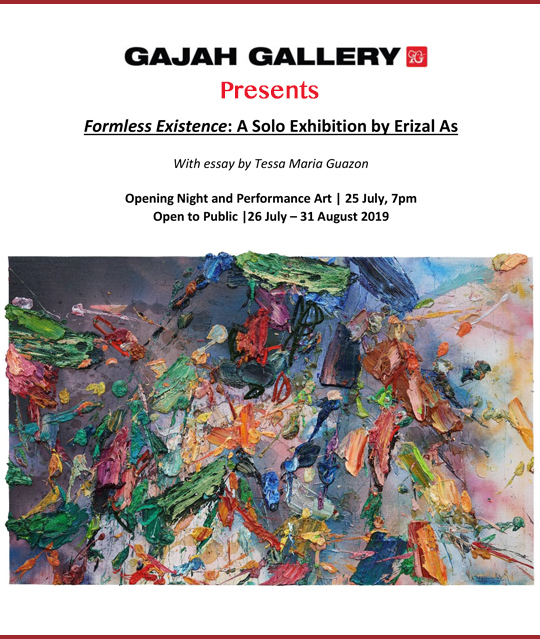

‘Formless Existence’ : A Solo Exhibition by Erizal As.

Published by Sugar & Cream, Tuesday 23 July 2019

Curatorial Text by Tessa M. Guazon, Images Courtesy of Gajah Gal. Yogyakarta

Gajah Gallery Yogyakarta : 25 July – 31 August 2019

Artist Statement : Erizal As

This exhibition is a continuance from another from my past, titled HUMANITY that opened in December 2017. In it, I discussed identity and the essence of being human; I sought to embody the values of humanity in my work- notions of theism, religion, righteousness, truth, justice, and culture.

Tolerance and Intolerance, 2019, acrylic and oil on canvas, 195 x 305 cm

In this exhibition, I am instead challenging the existence of these values. I am questioning the intentional negligence of these virtues for the sake of personal agenda that is propagated by those in power. The contradictory nature of the institutional disregard for rules while imposing them on the masses is, in my opinion, the leading disease of current society. The corruption and even extinction of those values once held so dear plagues and burdens my mind.

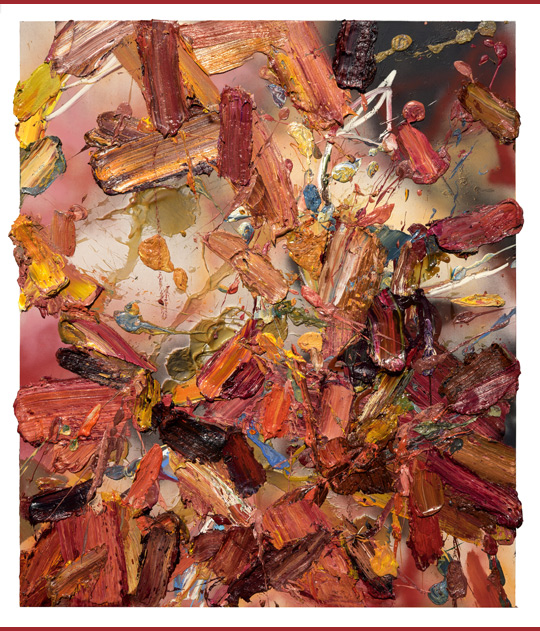

Neo, 2019, oil on canvas, 180 x 180 cm

My current understanding of abstract art is thus encapsulated by an existence that holds no form, or in short, a formless existence.

Ambitious, 2019, acrylic and oil on canvas, 200 x 180 cm

It is through the process of trying to comprehend the integrals of abstract art that divulges that Formless Existence to me. These ‘non-representational’ existences differ from searching for representation in a formless state. I have learnt that abstract art complies with its own language and I try to portray that same language the best that I can.

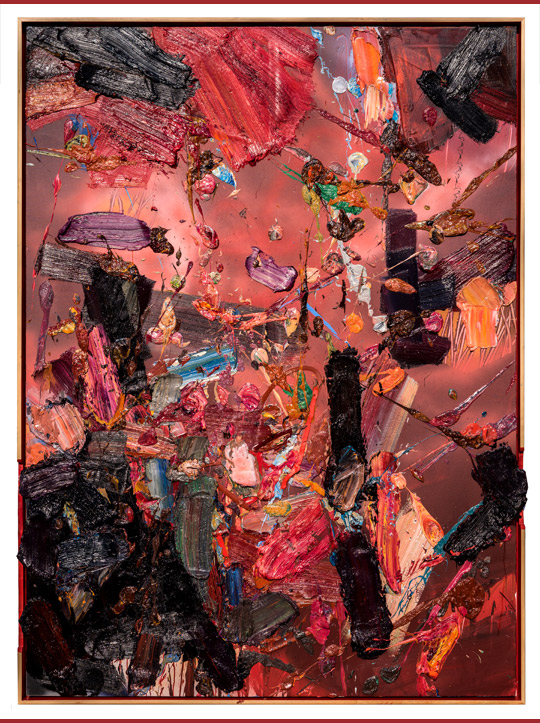

Vulgarity, 2019, oil on canvas, 230 x 170 cm

Of course, exploring the varied potentials of diverse painting techniques remains a deep interest of mine; it is, in fact, one of the discerning factors that has pushed me to shift my practice into more of an intrigue into abstract form seen through the different realms if visual aesthetics.

Menolak Batas, 2019, acrylic and oil on canvas, 230 x 170 cm

I purposely give meaning and place significance onto the body of paint that spills over the border of canvas. I manipulate the paint into something that is defiant, an entity that has its own will. This works in contrast to the frame around it as a metaphor for the boundaries, rules, and laws that bound us all against our will.

CEASELESS TRANSLATION: ITERATIONS OF ABSTRACTION

by Tessa Maria Guazon

Two short video clips on artist Erizal As’s Instagram show him working large canvases: one where he applies broad swaths of paint with a wide, flat brush on a nearly finished work, and another where he splatters paint with a palette knife on a yet unfinished piece. His canvases are propped against a wall, his movements are close to them and in the latter clip, his arm forms a half-arc that almost touches the canvas. The videos preview his suite of works for this exhibition: textured grounds of oil and acrylic whose undulating movements direct the eye to restlessly roam the pictorial field.

These recent oil paintings are explorations of densities – they summon vision in tense circuits across tracts of colour and form. They are most engaging in large scale format because sheer size proffers an expanse of visual range and depth. Their expressionist palette expands retina’s reach through forms that sweep into, overlap, and entangle with each other as they accrete into bulk. Erizal’s impastos form a core that branches out into drips, blots, streaks and cords of vibrant colour. The underlying ground reveals a lighter gossamer field, hues either thinly applied or air brushed.

Memberi Ruang- Giving Space, 2019, acrylic and oil on canvas, 230 x 170 cm

The works speak to the artist’s fascination with medium and the power of form to evoke images and stories. They articulate the infrastructure of form by devising movement, tactility, and depth to convey visual experience. One can prematurely surmise that this current exhibition is simply another exploration of the formal aspects of painting, but they are evidently a relentless examination of depth and field to articulate a visuality rooted in an art practice. The pieces condense movement through material that are otherwise static, the mediums of acrylic and oil. This is achieved by fusing lines, shapes, and texture into dynamic composites.

This essay is a narrative around Erizal As’s art practice, from his early works of 2007 to his subsequent transition into a decidedly abstract style. Close readings of representative pieces from past exhibitions will be made to propose an underlying strand that links the shifts in artistic choices. These transformations will be located against the context of the art world the artist navigates, from studies and training in Padang Panjang, West Sumatra to his fine arts training at the Institut Seni Indonesia (Indonesian Institute of the Arts), through his subsequent relocation to Yogyakarta. These localities will then be situated within the larger sphere of Indonesian contemporary art and its currency in Southeast Asia and the rest of the world. The influence of a local world in iterations of artistic styles will be emphasised. How does an artist simultaneously mediate this local world and the global art circuit through individual choices made across the span of an artistic career? How do facets of this often fragmented or split local world (I refer to both the context where art is made and circulated, and the sites of belonging to which artists identify) articulated in art works whose styles are obvious departures from tradition and yet are still heavily permeated by them? By examining the artistic paths that Erizal As had taken, we reflect on artistic choices, the manner whereby art is perceived, and how art practice itself is shaped by forces rooted in the larger world where art circulates.

Presented by Som Santoso

In a recent studio interview, I asked Erizal whether the shifts in artistic style are consciously made. He replied he noticed that these changes happen in cycles of five years. Alongside the numerous canvases propped on his studio walls, he showed me the tools of his craft – brushes, palette knives, tubes, canisters and stubs of paint, among others. He mentioned he is most comfortable working numerous canvases at the same time, that his vibrant palette is not decided beforehand, and the movements by which he covers his canvases with textured forms are spontaneous, almost subconscious.

Thick strokes agglomerate into each other – tiled impastos are either joined or broken up by strings or streaks of paint. There is an almost frenetic coagulation of paint on canvas: thick vermilion, coral, salmon and rose are punctuated by verdant greens and nocturnal blues. Some strokes even go beyond the edges of the frame. Others have blotches of Prussian blues, as if to mark a centre or a core. The more interesting pieces incorporate organic but unidentifiable forms that appear to combust or dissolve within our visual field. They emanate from a mass (more like the pith of a fruit), and the thinner lines that surround them function as cues for visual direction. Random lines are drawn over and underneath this cluster of densely applied paint. Thick clusters of form and thinly rendered ground meld together and hint at cosmic cycles as well as the flourishing and decay inherent to nature. We can trace a few of these visual devices to Erizal’s solo exhibition Lines Project. The works for this 2007 exhibition are illustrative and highlight his painterly persuasions.

Lines Project showcased variations of the human figure, objects, and landscapes presented in a quaint, even fantastical manner. Erizal draws his figures with a flourish through sweeping lines to capture the graceful arc of bodies. An example is Amour, a pencil and acrylic composition of a figure reclining against a white ground, almost floating on air. The limbs contrast with the figure’s long hair and right hand, rendered in more detail compared to the rest of the visual elements. In this work, we recognise Erizal’s daubs of paint in feather gray and crimson red, as well as transparent strokes in wisps of light yellow and pale blue. The artist experiments with scale in other pieces for the exhibition, painting globules of fruits draped on or cascading against white forms that at first glance, would appear like mountains or clouds. The Pesona Anggur series has a playful air, white boulders and cumulus clouds becoming receptacles for clustered globules floating against fields of blue that is the shade of the clearest, calmest view of the skies.

While the works reveal forms we can identify, several of them show a predisposition to abstraction. Curator Rizki Zaelani describes the process by which Erizal produced his images on canvas: “an almost impromptu and spontaneous deliverance of ideas and thoughts that sometimes can even be thought of as wild.” Zaelani also wrote about Erizal’s preponderance for drawing out forms from mass through a process he describes as “the logic of the sketch”, a “manifestation of ‘big-scaled lines’. While this reference to line or the ‘logic of the sketch’ seems unclear, we intuit it to be somehow related to the manner forms are coaxed out of a mass through the fine filaments of line and the arching flourish by which they are drawn. The masses whether sweeping strokes of paint or amorphous and biomorphic shapes of colours are rendered borders to finally arrive at a form. Erizal’s linear renderings are fine, quick and like his brush strokes, they assiduously direct the eye to meander across the picture plane. In this 2007 exhibition there are two works of acrylic and pencil on canvas titled Abstraction that are precursors to his 2016 exhibition of disfigured portraits and subsequently, to this 2019 exhibition of gestural forms.

His Refiguring Portraiture exhibition showcase portraits whose heads and faces have been blurred and marred by impastos. The series reflect on the artist’s observations of people’s public personas and their inscrutable nature. Overall, these works channel both the resilience and frailty of the human spirit in the way our faces and physical bodies relay these fluctuating states to the world. We discern in both Erizal As’s portraits and landscapes a transition between what we can generally refer to as representational and abstract styles. It is not a novel approach yet it presents an interesting lens through which to view the development of modernism in Indonesian art. Early on, the divide between these two styles of painting can be traced back to the cities of Yogyakarta and Bandung. Abstraction emerged and developed at the fine arts faculty of the Institut Teknologi Bandung (ITB). It was perceived as an emblem of the West and was considered detrimental to the search for and expression of national identity.

While the reverberations of this divide are less felt today, it is interesting to see how artists from other cities not considered centres of art mediate this art historical juncture. Jim Supangkat recounts that the art scene in Indonesia while centred in the big cities of Jakarta, Bandung, Yogyakarta, Surabaya, Denpasar and Ubud, artists undertake activities that succeed to blur the boundaries between these cities or the so-called centres of art. This results from artists knowing each other and exhibiting together. This early observation highlights the important role of artists’ mobility in relation to other locational positions such as art education and training, institutional affiliations, as well as the role of state agencies and private entities in the development of contemporary styles. Mobility even becomes more salient when we note that Erizal As and many others who now live and make art in Yogyakarta, are from other parts of Indonesia. Perhaps it is a conception of the ties between origins and the world beyond that makes an analysis of artistic choices more complex.

Erizal painted two landscapes for the 2018 exhibition Landscape’s Legacies – they were titled Matahari Pagi (Morning Sun) and Tekstur Alam (Nature’s Texture). Landscape’s Legacies considered the enduring influence of the pioneering landscape painter Wakidi. Wakidi was born in Plaju South Sumatra, the son of migrant farmers from Semarang. He trained briefly in Semarang with a Dutch artist, Van Dijk. He studied at the Sekolah Rajah (School of Kings) and began teaching from 1908 until his death in 1979, both at institutions and privately, at his home. He lived longer than most of his Mooi Indie compatriots, who did not teach or live through Indonesia’s independence. Katherine Bruhn’s curatorial essay weighs in on Wakidi’s legacy and traces the practices of West Sumatran artists to the Minangkabau traditional understanding of the world.

The distinction Minangkabau people make between ranah and rantau is salient to this conception of the world. It is about the way men move in rantau (the world beyond) and how they eventually bring back honour, prestige or economic success to ranah. The ranah is comprised of the three regencies of Tanah Datar, Lima Puluh Kota and Agam; while rantau refers to lands outside Ranah where the Minangkabau reside. It is also significant to note the phenomenon of merantau, or Minangkabau men leaving ranah. Bruhn cites that merantau and the fact that the Minangkabau is the world’s largest matrilineal Muslim society, shaped the fact of the Minangkabau’s “disproportionate contribution to Indonesia’s intellectual, political and cultural history.” These contributions began with Wakidi’s landscape paintings of the early 20th century.

Matahari Pagi and Tesktur Alam show Erizal’s distinct style of abstraction. In the former, we discern the rising sun as a salmon blob in the upper portion of the canvas while mountains are represented as silhouettes in black paint over the textured mass. The latter directly references the alam of the Minangkabau world signifying “creation as an act of knowing and an expression of knowledge”. We can discern this provenance in Erizal’s artistic practice: not only through facets of the alam Minangkabau or ancillary references to motifs that refer to the Minangkabau pepatah-patitih which are proverbs and poems that speak about the immutable laws of nature, that change only through the will of God. These prominent motifs are pucuak rabang or young bamboo shoot and the kaluak paku or the fern leaf tendril. These motifs are visually expressed in the traditional arts of carving and weaving that are referred to in Minang pepatah. The proverbs Bruhn gives as examples illustrate how forms from nature reflect human behaviour. Passages describe the manner a purposeful life is lived, or how men should conduct their affairs in the world with fairness and justice. While these motifs cannot be readily identified in Erizal’s recent works, they are loosely translated through visual density and movement, as the vertical orientation of the pucuak rabang referenced in the symbolic peaks of his Matahari Pagi piece, and the dense profusion and dynamism of his Tekstur Alam painting show.

Artists who trained at the Padang’s Fine Arts High School speak about “feeling left behind and lost” given the variety of artistic approaches they encountered upon arrival in Yogyakarta. This is very true for artists who chose to settle there. Such an overwhelming sense of being “outdated” can lead to a purposeful search for an artistic approach and aesthetic expression that simultaneously speak to their Minangkabau roots and that also lives up to their new context of art practice that is Yogyakarta. The exhibition Landscape’s Legacies considers the influence of Wakidi and his paintings on artists in West Sumatra. Bruhn proposes that the works presented offers quite different regard of this influence: on one end is the “romanticisation of Wakidi as forefather of Minangkabau art history”; on the other is a “rejection of Wakidi’s central position”. My own view is that the positions artists take with regard this legacy may not necessary fall into neat categories. Art historian Patrick Flores reminds us that there is greater complexity to the workings of modernity in Southeast Asia and it would do us well to go beyond the perceived divides between “figurative and abstract [art], nationalism and internationalism, conceptual-[-ism] against social realism”. I imagine there may have been numerous nuanced positions across the spectrum of a proposed visuality that considers the emergence of modernism in art in West Sumatra. Artists take on a range of approaches to assert themselves in the contemporary art world of Yogyakarta, especially since it has become a primary locus of Indonesia contemporary art production and theorising in recent years.

The Sakato Art Community which Erizal As now heads organises annual exhibitions. Bakaba 7 took place in 2018. The exhibitions the group organises function as platforms where they are able to look back and bring forward their Minangkabau roots. The diversity of artistic approaches and visual languages evident in the works for these exhibitions show that while such developments are partly about ‘bringing back’ what has been accomplished in the rantau (the world beyond the ranah). These are not essentialist lenses to frame identity but active interventions on how it is imagined. As Supangkat noted, group exhibitions bring together artists from far flung areas in Indonesia, and these are instrumental in breaking down barriers between cities, making ambiguous their positioning as either centres or peripheries of art.

This identity in flux may be the core of Erizal As’s quest to understand what he calls ‘non -representational existence’, or what he enigmatically labels ‘formless existence’. He mobilises form to explore this idea, in the process looking back to tradition, unpacking and re-articulating it in ways that respond to present contexts. These individual mediations not only locate the artist in the Yogyakarta art scene but also shines a light on forces within the art world and beyond, those that exert influence on the making, reception and circulation of contemporary art not only in Yogyakarta but also in Southeast Asia and the rest of the world. Incrementally, they become important signposts for institutions, agencies or even the art market to locate artistic practices historically. This can perhaps influence modes of collecting, steering them towards a more historically informed trajectory and less away from a profit oriented path. This artist’s quest after all goes beyond the rudiments of form – it is centrally concerned with location within a rapidly expanding yet paradoxically shrinking world, an act of ‘bringing back’ or grounding as the Minangkabau persistently do.

5.97K

20/02/2026

5.97K

20/02/2026

ROYAL COPENHAGEN INTRODUCES IRIS FOR SPRING 2026 COLLECTION

Royal Copenhagen unveils Iris for Spring 2026 — a softly coloured porcelain collection designed to bring warmth and effortless elegance to your table.

read more 1.59K

20/02/2026

1.59K

20/02/2026

DAVIDE GROPPI – ONEOFF BY OMAR CARRAGLIA

OneOff by Omar Carraglia for Davide Groppi, the ceiling becomes a luminous canvas—where a single gesture sculpts gradients, colour, and atmosphere into...

read more 10.56K

09/02/2026

10.56K

09/02/2026

B&B ITALIA OUTDOOR COLLECTION 2026

B&B Italia’s Outdoor Collection 2026 reflects a seamless dialogue between interior comfort and outdoor living.

read more 9.49K

29/01/2026

9.49K

29/01/2026

NEMO EXTENDS A PERRIAND CLASSIC FOR EXTERIOR LIVING: APPLIQUE À VOLET PIVOTANT OUTDOOR

Nemo extends one of Charlotte Perriand’s most enduring lighting designs into the outdoors, introducing the Applique à Volet Pivotant Outdoor.

read more 82.25K

10/01/2025

82.25K

10/01/2025

W RESIDENCE IN SOUTH JAKARTA BY MICHAEL CHANDRA

Michael Chandra, founder of MNCO Studio Design has created the W Residence with an aesthetically pleasing, practical, and pleasant home from all...

read more 44.74K

11/07/2025

44.74K

11/07/2025

PELUNCURAN PERDANA LEGANO HOME MENGGANDENG AGAM RIADI DI ST REGIS RESIDENCE JAKARTA

Peluncuran perdana LEGANO HOME menggandeng Agam Riadi di St. Regis Residence Jakarta: menyatukan kemewahan dan jiwa dalam sebuah ruang.

read more