Indonesia: The Heart of Asia’s Most Vibrant Collecting Scene Part #3

Published by Sugar & Cream, Tuesday 02 August 2016

Text and Images courtesy of Art Stage Jakarta

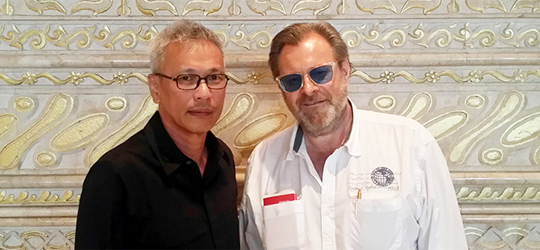

LORENZO RUDOLF IN CONVERSATION WITH WIYU WAHONO

Indonesian-born, German-educated Wiyu Wahono hails from an engineering background with a PhD specialty in plastics, and is one of the more cerebral and passionate collectors of contemporary art in Indonesia today. The former industrial consultant and lecturer at the Technical University of Berlin is on a quest to build an art collection that captures the zeitgeist of our time. Wiyu is a member of the Art Stage Jakarta Board of Young Collectors.

In parallel with the premiere of Art Stage Jakarta which will take place for the first time in Jakarta from August 5-7, 2016 at Sheraton Grand Jakarta, Lorenzo Rudolf , President of Art Stage of Singapore and Art Stage Jakarta have conducted several conversations with prominent art collectors from Indonesia. The conversation is to lead further understanding about Indonesian arts, the artists and as well as the collectors.

Here is the exclusive interview conversation between Lorenzo Rudolf and Wiyu Wahono

LR: Wiyu, you are known among peers for being one of the most thorough and intellectually-driven young collectors of Indonesian contemporary art. And yet I’ve also heard that it was your time in Germany that attracted you to art. Can you tell me more about your first encounter?

WW: When I was living in Berlin, my apartment was just steps away from the New National Gallery, and I would go almost every weekend. I really admired the building’s architecture by Mies van der Rohe, so I went to the Bauhaus Archive to find out more. There, I had a coup de foudre moment – it was the first time I saw a painting by László Moholy-Nagy, one of his compositions. Mind-blowing. That’s how I fell in love with art.

LR: How did your time in Germany influence your relationship with art?

WW: Wherever I went, I always had this great environment in Berlin to come back to. I travelled to Venice and visited the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. It was the period of Abstract Expressionism, so I saw many ugly paintings by Jackson Pollock, splash paintings and pieces with no colour. I was so confused! (laughs) They were so ugly compared to Indonesian art, I could not understand why they were displayed in prestigious institutions. That curiosity was the beginning of my journey into the art world. I wasn’t a collector yet, but I would go to all the exhibitions in Berlin, where the catalogues and papers were very informative.

LR: Given your contrasting Indonesian culture and background, what attracted you to the reductionist style and philosophy of the Bauhaus movement?

WW: I was fascinated with the reduction of everything to its essence. Mies van der Rohe lived by a philosophy of functionalism, and yet his balance of efficiency and rigidity with aesthetic design was incredible. The Barcelona Pavilion and Farnsworth House in Illinois blew my mind. Despite their minimalism, he managed to make the architecture look so good.

LR: So you started with a love for architecture, and moved on to art. How did you become a collector?

WW: I moved back to Indonesia in 1998, and started my own business. At the time, there were not much cultural activities – no classical music concerts, no exhibitions. I wanted to do something with art, so I sought out the famous Indonesian artist Teguh Ostenrik. He graduated from the University of the Arts in Berlin, and his artworks were collected by German museums and other institutions in Europe. In 2000, I bought my first piece. From there, I would go back to him regularly to buy more. That’s how I started collecting.

LR: Was that also the turning point of your interest in returning to your own roots, to Indonesian art? Or has your collecting direction always been equally open?

WW: No, in the beginning it was only Indonesian art. I learned about social responsibility from the Germans, it’s something my art friends and I discuss frequently. Right from the beginning, I thought about how I could add value to the Indonesian art world, and it occurred to me that I should support all the young Indonesian contemporary artists that were not necessarily market favourites, but were making very good work. I started with paintings and sculptures, and only changed tack in the mid-2000s.

Jompet Kuswidananto, Java

LR: Your collection is quite linear; it has a clear focus – has that always been the case? If not, how did you arrive here?

WW: At first, not yet. Perhaps because of the German influence, I found works that were too colourful old-fashioned. When I became more active in the art world, I set out to learn about contemporary art very systematically. I wanted to know what defined a collector, why did human beings collect art? What gave birth to contemporary art? How did it become today’s mainstream? These basic questions drove me forward. I tried to learn from other people in the art world, but there were many obstacles, so I decided to do it myself. I went through the catalogue of every exhibition, but it didn’t satisfy me because it was not a systematic learning process. When I got my first art theory book, I knew that it was what I had been looking for. Even though my command of English was insufficient for such complex essays, I was obsessed. Sometimes I had to read the text a few times to understand it properly. However, being able to grasp the true spirit of contemporary art triggered a change in my collecting process.

LR: Was there a certain theme or direction that you had chosen to shape your collection?

WW: I realized that in the 20th century, art was strictly medium-specific. It had to be canvas for 2-D and sculpture for 3-D art, until Harald Szeemann’s 1968 exhibition “When Attitudes Become Form”. Thus began a rebellion against medium-specificity, which paved the way for contemporary art. I also learnt that art’s function is not to depict beauty. The so-called “form over content” has died. Instead, in contemporary art, context is the major issue. The visual effect is secondary. And then I said to myself, “Wow Wiyu, you need to change the direction of your collection.”

LR: Well, when you were in Germany, Joseph Beuys must have made quite an impression, no?

WW: Exactly, encountering Joseph Beuys for the first time was confusing for me, but much later, I also learnt that conceptual art could not find proper appreciation in the wider public because of two major disadvantages: it was over-intellectual, and theory-heavy. People felt like they were not intellectual enough to appreciate conceptual art; it got left behind and eventually regarded as old-fashioned. That’s why a lot of contemporary art focuses not on the concept or idea, but the context.

Tromarama Ting 2008

LR: Yes, but in your case, don’t you think one must also be willing to accept this challenge, and overcome it through personal effort?

WW: I’m still very against conceptual art, because I feel that our history is wretched – it only goes in one way and never comes back, so what has happened in the past is passé. At the beginning it was so difficult for me to differentiate between an artwork that was idea-driven and one that was message-driven. For example, is it the concept of the art, or is it what the artist is trying to convey? That ability to differentiate took me some time, but knowing how to discern between conceptual and contextual has helped me so much in the way I collect art. I approach contemporary art with the same frequency.

LR: This intellectual journey you’ve embarked on, diving deeper and deeper into the history and theory of art – how has it impacted your collection?

WW: I talked to many big art collectors, and they spoke of the zeitgeist. A good artwork epitomises the spirit of its time. That’s why I always say collecting art is an intellectual experience rather than a sensory experience, because one is forced to analyse and capture what the zeitgeist of today will be perceived as in the future. I know for sure that computers, technology, is one of them. They have changed our lives completely. Globalisation. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Nelson Mandela’s release from prison. The student massacre in Tiananmen Square. The collapse of the Soviet Union. All of this changed the world. I thought to myself, globalization will definitely be seen as the zeitgeist – it has to be in my collection.

Another one: identity as a context. Before the 60s and 70s, the world was largely dominated by white males. Everyone else was inconsequential. Gender inequality was a non-issue. It was only the identity politics movement of the 60s that allowed people to gain an increase in self-awareness which spread to the world, and the art world. Art was no longer dictated by the tastes of the Western world. There was no longer a monopoly on the definitions of Modernism. I was so fascinated to learn about the world changing due to identity politics, I knew it would definitely be part of the zeitgeist. So I really focused on it.

Granular Synthesis, Kurt Hentschlaeger & Ulf Langheinrich.

LR: You’re a purist who believes in content, a collector who champions the independence of art from market forces. Apart from the earlier topics discussed, one of the biggest factors for change and globalization is also economic development and neo-liberalism, which has given the market a more dominant stake in the art world. What does that mean for you as a collector?

WW: Some collectors measure their success based on the appreciating value of their collection, but this is subject to the fluctuating and unpredictable movement of the contemporary art market. It’s beyond our control, and that made me realise that to only focus on the commercial value of the works is very dangerous. Of course, I would still like to purchase works that are very affordable at the start with growing demand, but my ultimate decision to buy is not driven by the economy. I also believe that artworks which embody the zeitgeist will sustain and grow in value. In 50 years, people will say, this is it – the truth. I hope that by concentrating on this, I’ll make a bigger profit than people who are only projecting 2- 5 years ahead.

LR: Will you take the risk of sharing today which artists will be the zeitgeist in 50 years?

WW: (laughs) Tintin Wulia is one of them. Her work deals with issues like geopolitics, globalization, hybridity of culture, all of which is very relevant to our time. Also, if you ask me: Jompet [Kuswidananto], with his syncretism of Indonesian history, hybridity of Dutch-Javanese culture, issues of identity, is very interesting. He creates artworks that are not medium-specific. The American Fluxus artist Dick Higgins coined the term “intermedia” for art that could not be strictly defined. I was the first collector to buy his work, and the first time I saw it, I thought, this guy is smart. I could see all the ideas: history, post-colonialism. Jompet is certainly one of the really good artists that the market hasn’t quite latched on to.

LR: Last question. What is the first step for someone who is interested in collecting art?

WW: Buy the first piece that you like. Don’t think about buying the wrong one. Lots of people will say, go around first and watch and learn before you buy, but I think once you buy the first piece, the fire starts burning. It brands you. You’ll feel so good because it becomes your defining moment as a collector. Don’t wait – if you like art, buy the first piece.

LR: Thank you.

1.05K

03/07/2025

1.05K

03/07/2025

DARE TO LISTEN! JBL FESTIVAL SIAP MENGGUNCANG JAKARTA – 13 SEPTEMBER 2025

Dare to Listen! JBL Festival Siap Mengguncang Jakarta pada tanggal 13 September 2025 dengan kehadiran musisi papan atas: Slank, Ari Lasso, Tiara Andini,...

read more 825

03/07/2025

825

03/07/2025

CIERRE1972 (2025 COLLECTION) - COLLECTION25: PART 1

The 2025 Collection by Cierre1972, which was on display at Salone del Mobile 2025, combined Italian craftsmanship with a global appeal through its bold...

read more 12.09K

17/06/2025

12.09K

17/06/2025

JAIPUR RUGS X PETER D’ASCOLI PRESENTS THE GILDED AGE COLLECTION (2025)

The Gilded Age collection by Jaipur Rugs X Peter D’Ascoli channels the decadent glamour of 19th-century design into bold, hand-knotted rugs that exude...

read more 10.83K

12/06/2025

10.83K

12/06/2025

MOLTENI&C 2025 COLLECTION – THE COLLECTION BY YABU PUSHELBERG, GAMFRATESI, UNIFOR X LSM

MOLTENI&C 2025 COLLECTION – THE COLLECTION BY Yabu Pushelberg, GamFratesi, UniFor x LSM

read more 74.62K

10/01/2025

74.62K

10/01/2025

W RESIDENCE IN SOUTH JAKARTA BY MICHAEL CHANDRA

Michael Chandra, founder of MNCO Studio Design has created the W Residence with an aesthetically pleasing, practical, and pleasant home from all...

read more 33.43K

16/05/2017

33.43K

16/05/2017

A Spellbinding Dwelling

Rumah milik desainer fashion Sally Koeswanto, The Dharmawangsa kreasi dari Alex Bayusaputro meraih penghargaan prestisius Silver A’ Design Award 2017.

read more